Perhaps it is a choice to act like an unmade bed; hair unkempt in a way that is tasteful to myself, eating with my hands, calm by my lonesome and loud in a group. Keeping a feral glow on my face, staying pure to my honesty. And too much so. My idiosyncrasies are often labeled unladylike, yet I find the concept of ‘ladylike’ antiquated.

Bernadine Evaristo spins a world of connections through poetry, all 452 pages of Girl, Woman, Other, in a narrative and verse structure that threads the lives of eleven women and a non-binary person together. Even though most of the women’s stories are set in England, histories of African heritage are vividly described from line to line. Evaristo’s work illuminates long-ignored lineages and experiences of Black women, from sexuality, to adolescence, to motherhood, and the infinitely mutable nature of human beings. She touches upon exclusivity in academia, queer relationships and experiences, motherhood, all but one arc in the African diaspora. Her characters are written so closely, and the verse style is akin to the staccato train of thought that we all have. Our constant changing of mind and unraveling stories are best described this way. Her experimentation with form allows us to follow the character’s development from line to line, which makes the reading process automatically paced out. This rhythm carries the magic through each intertwining story.

Twelve protagonists sounds daunting, but the way in which they are embroidered makes the book flow from one point of view to the other. A high school mentor named Shirley, that pops up in a character named Carol’s story, is given her own chapter afterwards.

“It’s not a collection of short stories, it’s a cohesive novel, just unusually structured. The characters have their own sections, but they bleed into each other.”

Quote from an interview with Evaristo

Evaristo wanted as many representations of Black womanhood as possible, and she deftly fit them into the book’s world. A Black woman attending Oxford University wishes to quit immediately after experiencing the othering of an almost all-white academic cohort. The characters are shaped so vividly; Amma, a lesbian playwright with a constant influx of lovers, freely creating and living as a gay British Black woman. Amma is our first character, and is eerily similar to the author in that she creates a hit play forty years after beginning to write. After the release of Girl, Woman, Other, Evaristo won the Booker Prize and finally garnered the readership and visibility that she deserved after forty years of writing novel after novel and working other jobs.

The realities of modern game-like dating apps, how a character feels when men perceive her as not gorgeous, but not ugly come out in the character Yazz’s story. Evaristo succinctly describes the:

“Swipe-Like-Chat-Invite-Fuck Generation where men expect you to give it up on the first (and only) date, have no pubic hair at all, and do the disgusting things they’ve seen women do in porn movies on the internet.”

This description is prescient today, as many girls fear the expectations of men that are objectifying and unrealistic. She continues to unravel female identity against the online quintessential sex object:

“Even though she’s considered reasonably attractive (as in not 100% ugly), with her own unique style (part 90s Goth, part post-hip hop, part slutty ho, part alien), she’s having to compete with images of girls on fucksites with collagen pouts and their bloated silicone tits out”

As a rather petit girl without large breasts, I used to wear push-up bras that pushed absolutely nothing up and left strange gaps of air where fabric clung and created a funky shape. Reading Yazz’s chapter, especially since it is set at the time of university, soothed that experience of mine because it’s mirrored in fiction. Evaristo’s fictional world pulses with these feminine conundrums of perception, both self-perception and perception by others. Even though I cannot understand the Black British woman experience because I am a white woman, there is a universality to the confusions of femininity. As somebody who does not fit the definition of ladylike, her characters’ dynamic personalities soothe my insecurities that flower when I don’t fit in.

Intersectionality is examined through each cohort of characters, with about three to four a section. During Yazz’s chapter at university, each friend within her group experiences life differently. Characters vary in wealth, religion, and skin color. There is a non-binary character, Morgan, who ends up becoming a motivational speaker on gender non-conformity. Their story is intricate, following their partner’s transition to female as well. The collection of subjective, differentiated experiences in Girl, Woman, Other is shown through each person’s histories. They eventually interconnect, in the end, at Amma’s play premiere. Some characters are close friends, some are mother and daughter, such as Amma and Yazz, and some are grandmothers.

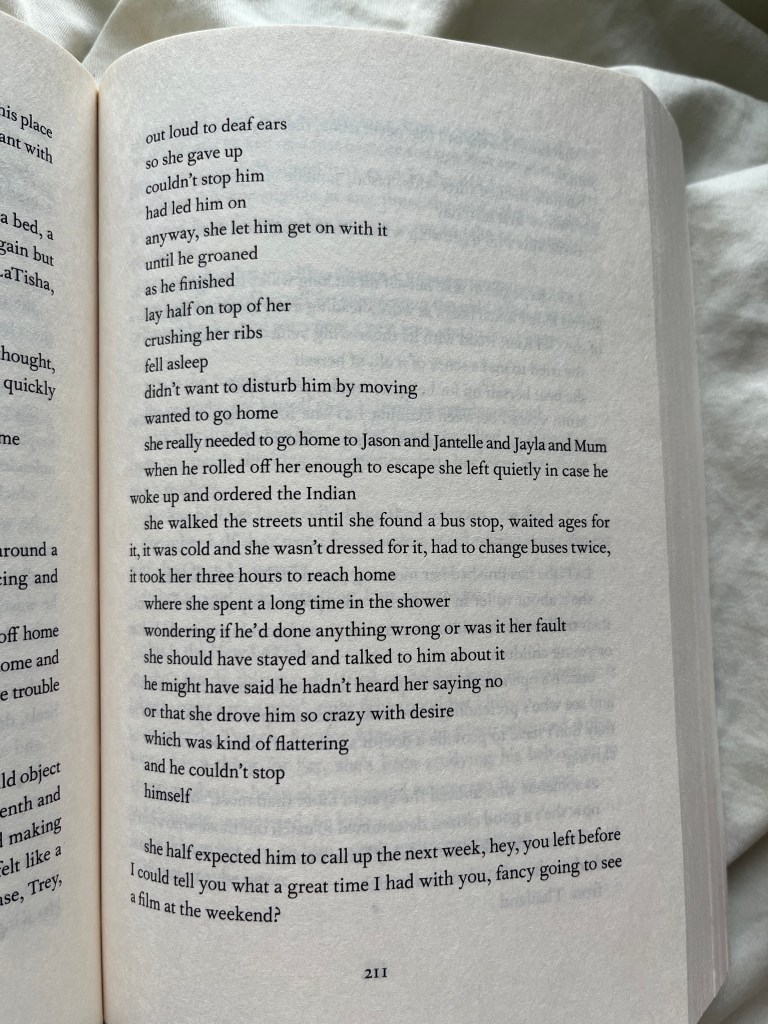

The novel’s experimental structure compels one to keep reading. Each story is told in verse, with line breaks and no full stops until the end of that character’s section. Intense moments in a character’s life, for example, we could see shorter lines, akin to a racing train of thought. This format in the context of traumatic events in a character’s life shows the breathlessness of fear, and the fragmented nature of shock.

Evaristo’s novel helps me learn what these perspectives of womanhood, gender, class, religion, and race are like. As a mixed-race British woman, She shares her heritage and experiences in videos online. Clad in a multicolor, multi-patterned blazer, she walks us through her tips for getting writing published in a Vogue Visionaries pseudo-class video on YouTube. In five chapters, she chronicles her writing career, all forty years until she won the Booker Prize in 2019. Her confidence is akin to the lovely narrator of Girl, Woman, Other: a steady, genuine, sure tone. She unfurls essential details about the publishing industry, guiding new writers in a modern direction. The path to living as a writer is obscure; devoting one’s life to art often yields little income. In a world that grows more expensive with the day, many choose other jobs and let their passions dissolve.

She imbues the viewer with determination, that dutiful, purely impassioned writing will result one day in glowing success. In her case, she worked until she became the first Black woman to win the Booker Prize. It is a literary triumph and a historical step forward. Her immense talent to capture twelve different lives and trajectories lives on in bookstores, in print and online.

Leave a comment